Welcome to the first post in a three-part series of blogs which will address:

- How to structure Analysis of Competing Hypotheses

- Moving past STIX 2.1 Opinion Object

- Introducing the Hypothesis Object

In this first blog post we will look at what Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) means and how it can support security analysts.

An introduction to ACH

A good security analyst uses a portfolio of known structured techniques, methods and skills that support them in their job. This allows them to work with and make sense of large amounts of data.

One of these is techniques is Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH). Put simply, ACH is a method analysts can use to evaluate hypotheses against a given range of evidence. Intelligence vendors, producers and consumers use ACH to evaluate a threat based on the available evidence.

During an investigation, analysts may need to identify inconsistencies across a set of hypotheses. Using ACH improves an analyst’s ability to assess and validate an issue with an assertion that has been tested for confidence.

How ACH is Currently Applied

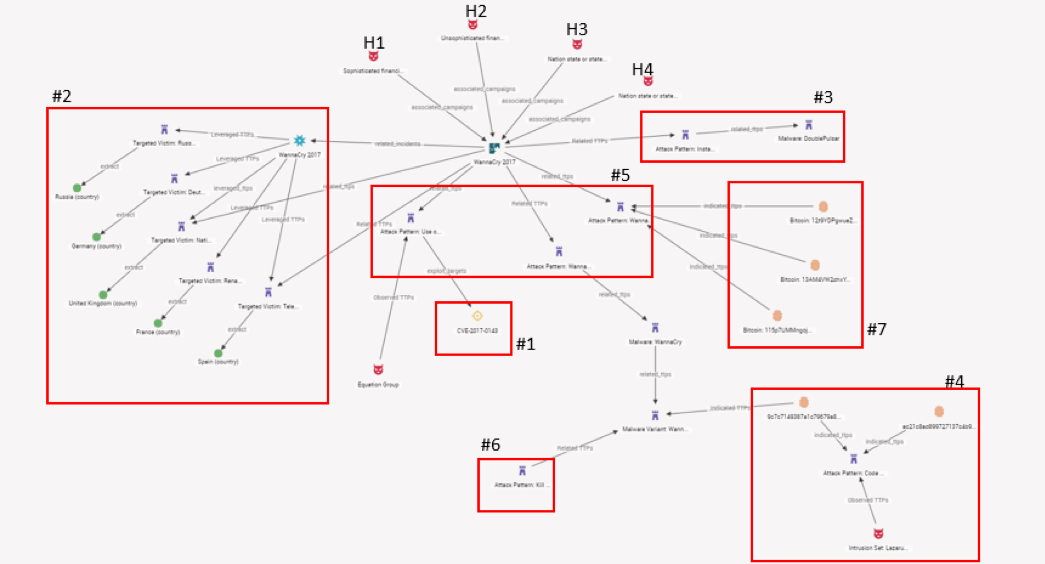

Cybersecurity intelligence provider Digital Shadows gave a real-world example of ACH in action in May 2018, when it modeled and published a report about multiple competing hypotheses surrounding the WannaCry ransomware incident. The malware impacted enterprise networks and organizations across the globe. Hours after WannaCry occurred, many public and private companies within the intelligence community were attempting to identify and attribute the attack, these analysts hoped for a greater understanding of how and why the attacks took place.

Digital Shadows outlined four possible hypotheses about potential attribution and tested them against the set of evidence that became available during and after the incident occurred:

H1 - A sophisticated financially-motivated cybercriminal actor

H2 - An unsophisticated financially-motivated cybercriminal actor

H3 - A nation state or state-affiliated actor conducting a disruptive operation

H4 - A nation state or state-affiliated actor aiming to discredit the National Security Agency (NSA)

The evidence in this case are data points that the community learned or observed about the incident:

- Use of Eternal Blue Equation Group exploit

- Targeted globally-diverse victims

- Installed DOUBLEPULSAR backdoor

- Code similarities to North Korean malware

- No evidence of phishing vector

- Kill switch as anti-analysis feature

- Only three Bitcoin wallets produced

Taking Digital Shadows’ plausible scenarios about WannaCry origin, there are limitations in STIX (Structured Threat Information Expression) that make it difficult to structure the process of conducting and structuring ACH.

In the image above, the groupings show the evidence and the various hypotheses, but one can see that there is no way in STIX for a producer/consumer/collaborator to structure and convey the results of having tested multiple hypotheses at once. In its current form, STIX allows us to see a confirmed reality (for example: Threat Actors à Campaign; Indicators à TTPs; Incident à Targeted Victims). There is currently no entity that will represent an alternative view that would let consumers see competing hypotheses in a structured way.

At the time of Digital Shadows’ analysis, it was identified that H2 – an unsophisticated financially-motivated cybercriminal actor – was the strongest-scoring hypothesis from the evidence that was available. After using the evidence to test a set of hypotheses, there is still no way to structure which hypothesis scored strongest.

Identifying the Problem and Wrapping Things Up

While ACH brings many benefits, the main problem with using the approach is that there is currently no way to structure the process of testing evidence against a set of hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, etc.). As a result, producers of intelligence often create multiple competing hypotheses around a given threat hoping to identify the strongest hypothesis, i.e. the one most supported by the available evidence. If the process of testing evidence can be structured more effectively, the benefits of ACH will become even more apparent.

Part two of this series will address STIX in more detail and some of the limitations in structuring ACH. Make sure to check our blog for the rest of this series.

We hope you enjoyed this post. Follow us here for more interesting reads on Cyber Threat Intelligence or check out our resource section for whitepapers, threat analysis reports and more.