When new technologies and systems launch, developers and defenders find themselves disadvantaged relative to threat actors seeking to exploit those systems because cyberattack patterns to which organizations can effectively implement resources are not yet established. However, even with new technologies and implementations, threat actors establish patterns to cyberattacks early, which are then repeated with minor changes. Identifying tactics, techniques, and procedures of early outlier cyberattacks provides an advantage, highlighting best practices ahead of further threat actor activity in new technology.

Early Large-scale Cyberattacks Likely Serve as Models for Threat Actors Adopting Similar Tactics and Techniques Later

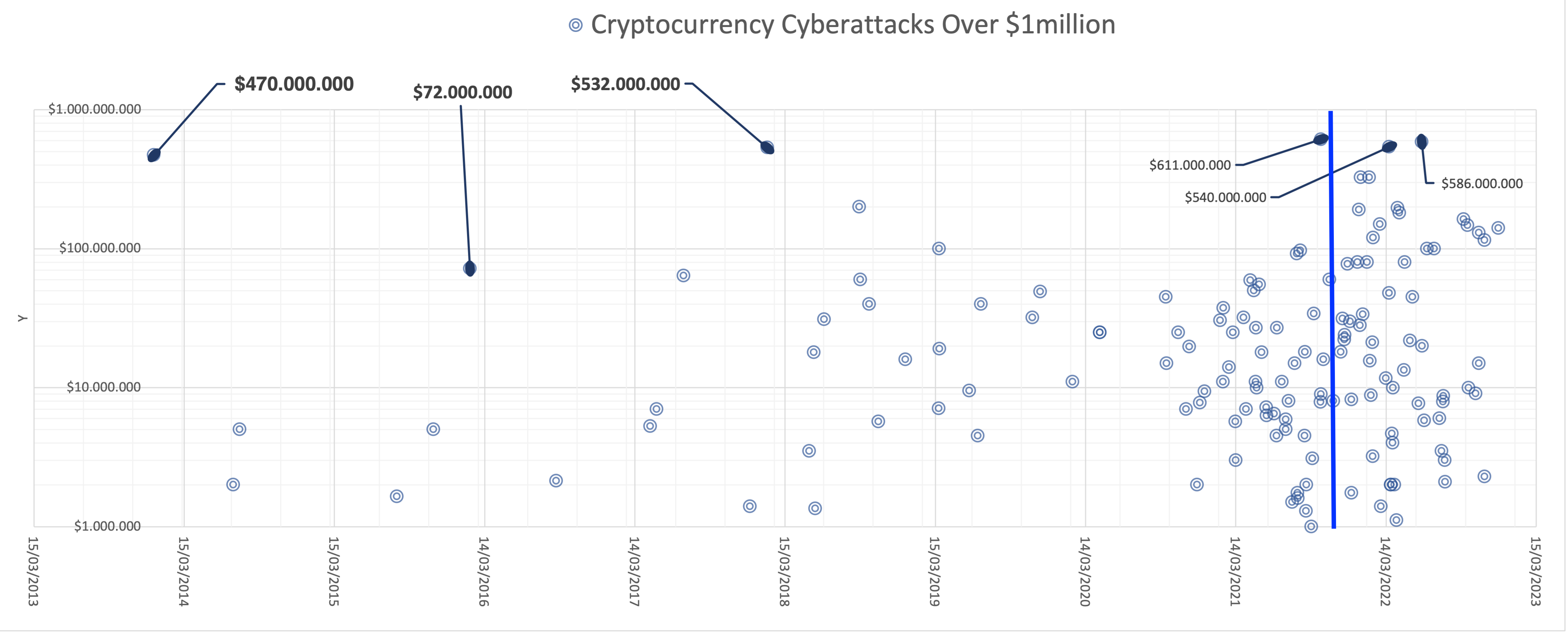

Analysis of successful early large-scale cyberattacks provides the evolving cyberattack patterns of greatest impact as they are being adopted by threat actors against new technologies. Three early cyberattacks remain outliers across the landscape of cryptocurrency cybertheft. A study of these cyberattacks demonstrates the new tactics and techniques that are further repeated in later cyberattacks forming clear patterns. Three cyberattack outliers of concern are the three datapoints furthest from the mean and furthest from their neighboring datapoints in Figure 1, below. All occur prior to peak Bitcoin market capitalization in 2021, all are against centralized cryptocurrency exchanges, and result in the largest quantities of Bitcoin converted and stolen. The cyberattacks either directly steal Bitcoin or successfully convert stolen cryptocurrency to Bitcoin yielding approximately 1.09 billion dollars combined (as measured using the Bitcoin price at the time of exfiltration for each cyberattack and any remaining assets sitting dormant that have matured with the price of Bitcoin). Most assets were not marked, frozen, or reclaimed so the successfully exfiltrated assets have further appreciated in value and are still sitting in threat actor-controlled wallets. For scale, almost $7.2 billion in cryptocurrency was stolen as of the end of 2022, reflecting total amounts recovered (1, 4). The three cyberattack outliers account for approximately 15% of total losses.

Key Management, Hot Wallet And Vault Configuration, Together With Smart Contract Code Validation Make Up The Bedrock of Emerging Best-Practices in Cryptocurrency

Financial technology platforms lacking cryptocurrency security best practices are at higher risk from cyberattacks imposing large loss. These best practices are confirmed by cyber threat intelligence, which is growing along with the volumes of cyberattacks against financial technology.

Figure 1: Three Early Cyberattack Outliers vs. a Cluster of Later Cyberattacks Producing Similar-Scale Losses 2009 and 2022, a map showing cryptocurrency cyberattacks

Between 2009 and 2022, a map showing cryptocurrency cyberattacks over $1 million scaled logarithmically to emphasize data clustering.

Bitcoin achieved an all-time peak price of 65,000 USD in November 2021, marked by the dark vertical line. Large-scale cyberattacks begin with hacks of the Mt. Gox Bitcoin exchange that occur between 2011 and 2014. From then on cyberattacks carry on at a steady tick, beginning to increase just prior to 2018. This is likely due to the initial significant price-bump Bitcoin experienced just prior. The odd gap observed just after 14/03/2020 can be explained by the initial wave of global lockdowns that occurred beginning about the same time. The large cluster of cyberattacks on the right-hand side shows repeating cyberattack patterns becoming established almost certainly a reaction by threat actors to cryptocurrency price increase. See appendix A for further discussion.

Wallets and Vaults: A Quick Refresher

Data analysis concerning large-scale (greater than $1 million) cyberattacks helps visualize how cyberattacks have become well established despite the large cryptocurrency market downturn that began in earnest in 2022.

1. Mt. Gox, 2011 through 2014 - up to 850,000 Bitcoin ($470,000,000)

Financial technology must undergo continuous testing, incorporating transparent vulnerability tracking to mitigate known weaknesses that can create highest risk. Privileged accounts must be monitored and maintained with the least privilege.

Vulnerabilities affecting poor design that integrates smart contract and wallet flaws are responsible by some measures for over 70% of large-scale cyberattacks through 2022. In 2022 the known-vulnerabilities vector alone was reported for 20-50% of hacks on cryptocurrency financial technology. (1)

A string of cyberattacks on Mt. Gox involved known vulnerabilities and possibly vulnerable code reuse. Mt. Gox’s hack represented the first cybertheft or hack of considerable scale in bitcoin’s history. (2, 3) The first initial incident was recorded on 13 June 2011, which was approximately one year after the first cryptocurrency retail transaction. (4) A string of further incidents occurred up until the exchange closed in 2014. The largest single transfer recorded is 261,383.7630 BTC. (5)

On June 13, 2011, the Mt. Gox bitcoin exchange initial compromise occurred via a machine owned by a recent auditor of Mt. Gox who may also be tied to an account of the platform founder. A lawsuit suggests a dictionary attack may have been used to guess the password of the auditor account. (6) Further reporting strongly indicates the auditor system was compromised via known credentials, which provided privileged access to the Mt. Gox exchange. The high level of access allowed the threat actor to steal private keys to a hot wallet -containers that remain connected to the network- and obtained privileged access to a nominal trading value, which they used to transfer bitcoin to their wallet.

Mt. Gox reported cybertheft across 478 accounts. Then on June 17, a message offering the Mt. Gox user database for sale was published to Pastebin under the username “~crazlestinger~”. Reporting indicates that vulnerabilities were present and known to the founder of the platform since at least the conclusion of this initial hack.

Later, in September 2011, two Russian nationals discovered existing weaknesses and leveraged an "unknown" vulnerability to gain access to an Mt. Gox server and compromised some of the primary signing keys used by the exchange to sign transactions. They siphoned bitcoins off slowly up until 2014. (6, 7)

Lawsuits indicate that the platform key architecture and/or design of Mt. Gox was the primary contributor for the string incidents that began with the 2011 hack. The Russian cybercriminals were able to launder the stolen bitcoin through their own cryptocurrency exchange BTC-e. Bankruptcy proceedings show the exchange claims 850,000 bitcoins were lost. 200,000 have been reported found or recovered, but only 1811 bitcoins can be reliably traced. (9)

The largest exchange at the time closed shortly after this second cyberattack. EclecticIQ analysts propose the person posting the database under "crazlestinger" was most likely not the same threat actor that compromised the auditor account or the other two Russian cybercriminals who were indicted. (7) The date of posting is not likely the same date as compromise so the known timeline of related events likely extends further into the past. Reporting indicates known vulnerabilities possibly remained present for up to a year or more. The extended timeline could have allowed multiple threat actors to exploit the exchange. Reselling the data to other threat actors helps obscure everyone’s identity. Redistributing stolen account data likely directly enabled further compromise of the largest bitcoin exchange at the time, which was an obvious high-value, attractive target. Trading information gleaned in hacks is commonplace among cybercriminal networks.

2. BITFINEX, 2016 – 120,000 BITCOIN ($72,000,000)

Threat models must consider compromise of primary signing systems to increase fidelity of primary key architecture design. Improved management and design of signing protocols helps to mitigate worst-case scenarios of incidents resulting in large-scale compromise and theft.

Key exposure increases to between 4-16% in 2022 and other sophisticated tactics and techniques rise to over 60% (1). The Bitfinex hack retains a more sophisticated kill-chain than most other large-scale cryptocurrency hacks. The Ronin Bridge cyberattack of 2022 is another example of a sophisticated cyberattack resulting in many hundreds of millions of dollars. (1, 10)

The original point of entry is unknown and to date, the majority of stolen funds remain in the original wallet. Reporting indicates that the cyberattack very likely took place over more than a year, but the funds were stolen in a single transaction and exfiltrated to a single wallet. (11)

The threat actor compromised more than one signing key used in a multi-signature protocol. BITFINEX held two keys and BITGO, an associated company, held a third (12). There was no further service in place to identify and block the large single withdrawal. Further investigation found no evidence of compromise of BitGo servers, (13) likely implicating compromise of the BITFINEX-side of the signing protocol.

EclecticIQ analysts propose the threat actor most likely either:

a) had to perform extensive reconnaissance on the network beforehand in order to identify the necessary privileged signing systems/protocols to further compromise, or

b) pivoted from some other node within the network that acted as the origin for the cyberattack –something that requires a longer cyberattack delta.

Both hypotheses involve greater sophistication and resources. The longer timeline and advanced techniques reported produced very little footprint in the form of IOCs; something expected of APT groups that have the financial resources and patience to use multiple obfuscation tools to hide their tracks. If an individual (lone wolf) threat actor is implicated, they must have been highly skilled and are most likely an insider threat possessing greater knowledge of internal systems.

Elliptic identified four concentrated campaigns to exfiltrate or launder some of the money since the original hack. (14) One IP address and the same email provider were used to create accounts over a short period for the movement of stolen funds. The United States prosecuted two individuals after the most recent movement of funds was observed. (15) Law enforcement officials were able to obtain an order to access a service provider that then provided access to a cloud account linked to the defendant, where private keys to an associated laundering wallet were stored. Initial analysis shows funds ingress from a plethora of laundering points (16). Movements of small funds continue to occur from the original main wallet.

3. COINCHECK, 2018 - 46,000 BITCOIN ($532,000,000)

Users must have transparency (on at least a high-level) into how Defi systems in which they participate are designed, to help shield them from high-impact cyberattacks seeking to exploit weak system design. Financial technology controlling large concentrations of assets must be provisioned with multi-signature validation.

Flaws in network design and protocol implementation account for approximately 18% of large cyberattacks by 2022. (1) On January 26, Coincheck experienced a cyberattack that targeted a primary hot wallet used by the exchange. The targeted wallet did not have multi-signature technology to provide further validation of transactions (17, 18). The original NEM tokens were sent to a threat-actor controlled wallet (19) on the same day of the cyberattack. A threat actor gained unauthorized access to the network through undisclosed means. (20)

The financial technology network architecture was designed around a proof-of-importance (PoI) consensus. (21) This process ensures all network nodes agree with each other when a transaction occurs and the advantage is that transactions do not require validation through processing power and also prevent 50% consensus cyberattacks.

The threat actor almost certainly gained access to a privileged machine on the network in order to circumvent the PoI protocol. This implicates a targeted phishing attack or further point of initial-entry in order to gain higher privileges.

Exfiltration via bitcoin began on February 1, 2018. The largest ever transaction from the wallet occurred on March 20, 2018 using Mosaic to obtain 1000 bitcoin. 4778 transactions complete the exfiltration phase via transactions that are almost all between $50 and $9000. (22, 23, 24)

A better practice includes restricting large concentrations of funds from building up in single hot wallets in the first place, because their availability almost always remains more vulnerable to exploitation attempts than cold storage that is offline.

North Korea is suspected of the cyberattack based on an initial 2018 investigation. (25) Russian cybercriminals are later implicated in a 2019 investigation because of malware-as-a-service variants found that are associated to Russian-based developers. (26)

Conclusion

High Impact Cryptocurrency Cyberattacks Impose Large Losses

The emerging best-practices in cryptocurrency include key management, as it applies to configurations of vaults and wallets, as well as smart contract code transparency and validation. In the first half of 2023 similar large-scale cyberattacks persist with great impact. Two unrelated cyberattacks account for over 72% of annual recorded losses against cryptocurrency platforms in 2023. The root causes of both cyberattacks also fall into two of the best-practice categories discussed here. Consistently focusing on the cyberattack patterns established from high-impact cyberattacks will greatly mitigate risks going forward to all involved. Centralized regulation is the most likely pathway forward for achieving minimum standards of cybersecurity.

Appendix A.

Since 2021 and further illustrated in Figure 1 – The other cyberattacks of a similar scale nearly matching the three hacks described in this report.

- The Poly network cyberattack resulted in most of the earnings being returned voluntarily.

- The 2022 Binance cyberattack resulted in most of the stolen funds being frozen by Binance.

- The FTX hack still involves numerous unknowns, but reporting points to an insider tied to a total transfer of approximately $400 million. (28, 29)

- The Ronin network hack of 2022 valued at over $500 million was attributed to a North Korea-linked APT group. (30)

A report providing further analysis of the data points included within this report can be found on our website. (27)

About EclecticIQ Intelligence and Research

EclecticIQ is a global provider of threat intelligence, hunting and response technology and services. Headquartered in Amsterdam, the EclecticIQ Intelligence and Research team is made up of experts from Europe and the U.S. with decades of experience in cybersecurity and intelligence in industry and government.

We would love to hear from you. Please send us your feedback by emailing us at research@eclecticiq.com or fill in the EclecticIQ Audience Interest Survey to drive our research toward your priority area.

You might also be interested in:

Polish Healthcare Industry Targeted by Vidar Infostealer Likely Linked to Djvu Ransomware

3CX Incident Attributed to North Korea; New LockBit MacOS Sample

Exposed Web Panel Reveals Gamaredon Group's Automated Spear Phishing Campaigns

References

[1] Dubief, “Call of DeFi: The Battleground of Blockchain.” May 24 2023 [online]. Available: https://bishopfox.com/blog/decentralized-finance-blockchain-battleground (accessed Apr. 25, 2023).

[2] Cryptopedia Staff, “Crypto Hacks and What We Can Learn From Them.” Aug. 15, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.gemini.com/cryptopedia/mt-gox-bitcoin-exchange-hacked (accessed: Apr. 28, 2023).

[3] Chainsec, “Documented Timeline of Exchange Hacks,” 2023. [online]. Available: https://chainsec.io/exchange-hacks/ (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[4] EclecticIQ Research Team “Attack Patterns Produce Growing Losses Targeting Mutual Vulnerabilities Endemic to Decentralized Finance.” Apr. 6, 2022. [online]. Available: https://blog.eclecticiq.com/attack-patterns-produce-growing-losses-targeting-mutual-vulnerabilities-endemic-to-decentralized-finance (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[5] Blockchain.com “bitcoin transaction.” Jun. 19, 2021 [online]. Available: https://www.blockchain.com/explorer/transactions/btc/84f96975ea88d317676771a482c71f39ff53beda790c89c07ae82e427b4d090f (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[6] CRAIG ADEYANJU, “Mt. Gox Vulnerability Covered Up by Founder McCaleb, Lawsuit Alleges.” Jul. 02, 2019. [Online]. Available https://cointelegraph.com/news/mt-gox-vulnerability-covered-up-by-founder-mccaleb-lawsuit-alleges (accessed: Apr. 26, 2023).

[7] USDOJ, “Russian Nationals Charged With Hacking One Cryptocurrency Exchange and Illicitly Operating Another.” Jun. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/russian-nationals-charged-hacking-one-cryptocurrency-exchange-and-illicitly-operating-another (accessed: Apr. 28, 2023).

[8] Wikipedia, “Mt. Gox” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mt._Gox#Security_breach,_user_DB_leak,_and_invalid_addresses_(2011) (accessed: Apr. 28, 2023).

[9] David Z. Morris, “4 Unanswered Questions About the Bitfinex Hack,” Feb. 09, 2022 [online]. Availablehttps://www.coindesk.com/layer2/2022/02/09/4-unanswered-questions-about-the-bitfinex-hack/ (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[10] Blockchain Explorer, “Addressbc1qazcm763858nkj2dj986etajv6wquslv8uxwczt.” Apr. 28, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://blockstream.info/address/bc1qazcm763858nkj2dj986etajv6wquslv8uxwczt (accessed: Apr. 28, 2023).

[11] Stan Higgins, “The Bitfinex Bitcoin Hack: What We Know (And Don't Know).” Aug. 23, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2016/08/03/the-bitfinex-bitcoin-hack-what-we-know-and-dont-know/ (accessed: Apr. 28, 2023).

[12] Clare Baldwin, “Bitcoin worth $72 million stolen from Bitfinex exchange in Hong Kong”, Aug. 03, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-bitfinex-hacked-hongkong-idUKKCN10E0KN (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[13] Elliptic, “Elliptic Follows the $7 Billion in Bitcoin stolen from Bitfinex in 2016.” May. 13, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.elliptic.co/blog/elliptic-analysis-bitcoin-bitfinex-theft (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[14] USDOJ, “Two Arrested for Alleged Conspiracy to Launder $4.5 Billion in Stolen Cryptocurrency.” Feb. 08, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/two-arrested-alleged-conspiracy-launder-45-billion-stolen-cryptocurrency (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[15] Slowmist, “Analysis of the $3.6 Billion Recovered by the U.S Government from the 2016 Bitifnex hack.” Feb. 09, 2022 [Online]. Available: https://slowmist.medium.com/analysis-of-the-3-6-billion-recovered-by-the-u-s-government-from-the-2016-bitifnex-hack-46abc296342d (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[16] The Hacker News “Someone Stole Almost Half a BILLION Dollars from Japanese Cryptocurrency Exchange.” Jan. 26, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://thehackernews.com/2018/01/coincheck-cryptocurrency-heist.html (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[17] Bloomberg, “Coincheck Says It Lost Crypto Coins Valued at About $400 Million.” Jan. 26, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-01-26/cryptocurrencies-drop-after-japanese-exchange-halts-withdrawals#xj4y7vzkg (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[18] Nem, “Account detail,” Feb. 07, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://explorer.nemtool.com/#/s_account?account=NCU63AYO6RS2ISG4UEP5CALTKVQOB4FUTYIYXUAV (accessed May 08, 2023).

[19] AFP, “Cryptocurrencies Fall After Hack Hits Japan’s Coincheck,” Jan. 26, 2018. . [Online]. Available: https://www.securityweek.com/cryptocurrencies-fall-after-hack-hits-japans-coincheck/ (accessed Apr. 28, 2023).

[20] Theo Stylianou, “Coincheck Hack and NEM: a cloud cast over the future of cryptocurrency exchanges?.” Feb. 26, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/coincheck-hack-nem-cloud-cast-over-future-exchanges-stylianou (accessed May 08, 2023).

[21] Nem, “Account detail,” May. 27, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://explorer.nemtool.com/#/s_account?account=NBEAUKXJLBJXXTPXN2OPIX3LZQWWZA56IQO2P5S3 (accessed May 08, 2023).

[22] Moonbeam, “Mosaic by Composable Finance.” NA. [Online]. Available: https://moonbeam.network/community/projects/mosaic-by-composable-finance/ (accessed May 08, 2023).

[23] Yoichi Tsuchiya, Naoki Hiramoto, et. al. “How cryptocurrency is laundered: Case study of Coincheck hacking incident.” Nov. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2665910721000724#fn7 (accessed May 08, 2023).

[24] Zheping Huang, “North Korea is a suspect in the world’s biggest cryptocurrency heist.” Feb. 06, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://qz.com/1199400/north-korea-is-suspected-in-the-530-million-coincheck-cryptocurrency-heist (accessed May 08, 2023).

[25] Cointelegraph Japan, “Asahi Shimbun raises doubts about whether North Korea was involved in coin check scandal.” Jun. 17, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://jp.cointelegraph.com/news/asahi-shimbun-reports-russian-involvement-in-coin-check-incidents (accessed May 08, 2023).

[26] EclecticIQ Threat Research Team. “Attack Patterns Produce Growing Losses Targeting Mutual Vulnerabilities Endemic to Decentralized Finance.” Apr. 06, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://blog.eclecticiq.com/attack-patterns-produce-growing-losses-targeting-mutual-vulnerabilities-endemic-to-decentralized-finance (accessed May 08, 2023).

[27] Krisztian Sandor, “FTX Hack or Inside Job? Blockchain Experts Examine Clues and a ‘Stupid Mistake’.” Nov. 14, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.coindesk.com/business/2022/11/14/ftx-hack-or-inside-job-blockchain-experts-examine-clues-and-a-stupid-mistake/ (accessed May 08, 2023).

[28] Elliptic, “$477 Million in “Unauthorized Transfers” from FTX.” Nov. 11, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://hub.elliptic.co/analysis/477-million-in-unauthorized-transfers-from-ftx/ (accessed May 08, 2023).

[29] US OFAC, “North Korea Designation Update.” Apr. 14, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://ofac.treasury.gov/recent-actions/20220414. (accessed May 08, 2023).

[30] Paulina Okunytė, “Hackers steal $420m-worth of crypto.” Apr. 05, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://cybernews.com/crypto/crypto-hacks-in-2023/ (accessed May 08, 2023).